This post is the first in a What Is… series. The idea is to explain different techniques, terminology and concepts related to spatial audio. This will range from the most common terms right through to some more obscure topics. And where better to start than “spatial audio” even means!

Spatial audio (with some exceptions) has generally been confined to academia but is rapidly finding applications in virtual reality (VR). There are even moves to bring it to broadcasting so it can be enjoyed by people in the comfort of their living rooms. As spatial audio moves from labs to living rooms it is worth exploring all of the different techniques that have been developed up to this point.

However, defining spatial audio can quickly become rather philosophical. For example, is a mono recording spatial audio? If I take a single microphone to a concert hall and record a performance then I have captured the sense of space, through echoes and reverberation, not just the performances themselves. This means that the space is encoded into the signal – we can tell if a recording is made in a dry studio or a cathedral. For the purposes of this series I will not be considering this to be spatial audio. Instead, I will be defining spatial audio as any audio encoding or rendering technique that allows for direction to be added to the source. How well this is reproduced to the listener will depend on the encoding and playback system but, in general, a spatial audio system will allow different sounds placed in different positions to be directionally differentiated.

There are a large number of different spatial audio techniques available and which one you want to use will depend on the final use. These techniques include (but are in no way limited to):

- Stereophony

- Vector Base Amplitude Panning (VBAP)

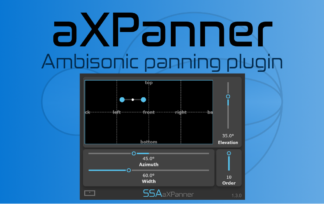

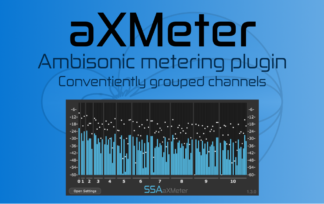

- Ambisonics and Higher Order Ambisonics (HOA)

- Binaural rendering (using HRTFs over headphones)

- Wave Field Synthesis (WFS)

- Loudspeaker diffusion

- Discrete loudspeaker techniques

Each of these will be explained in more detail in future posts but you can see from this non-exhaustive list that there are already quite a few techniques to choose between. To further complicate things, some of these techniques can be combined in order to take advantage of different properties of both. For example, Ambisonics and binaural can be combined in VR and augmented reality (AR) to give a headphone-based rendering that can be easily rotated (a nice property of Ambisonics).

Spatial audio techniques can also be divided between those that aim to produce a physically accurate sound field in (at least some of) the listening area and those that are not concerned with matching a “real” sound field. HOA and WFS can both be used to recreate a holophonic sound scene using an array of loudspeakers. Meanwhile, stereo and VBAP do not recreate any target sound field but are still able to produce sounds in different directions.

Whether or not the spatial audio technique is physically-based or not, we also have to consider the potentially most important element in the whole chain: the listener! All of these techniques rely on how we perceive the sound and there are any number of confounding factors that can take our nicely defined (in a mathematical sense) system and throw many of our assumptions out the window. Therefore, this What Is… series will also include elements of spatial hearing and psychoacoustics that are essential to consider when working with spatial audio.

So, spatially audio can take a number of forms, each with their own advantage, disadvantages, limits and creative possibilities. It is these, along with the technical and psychoacoustic underpinnings, that I will expand upon in upcoming blog posts.

If there are any aspects of spatial audio that you’d like to have explained then leave a comment below.